Kazakhstan — Wikipedia

Republic in Central Asia

Kazakhstan[b] (Kazakh: Қазақстан, romanized: Qazaqstan, IPA: [qɑzɑqˈstɑn] ( listen); Russian: Казахстан, romanized: Kazakhstan), officially the Republic of Kazakhstan (Kazakh: Қазақстан Республикасы, romanized: Qazaqstan Respýblıkasy; Russian: Республика Казахстан, tr. Respublika Kazakhstan),[4][13] is the world’s largest landlocked country, and the ninth largest country in the world, with an area of 2,724,900 square kilometres (1,052,100 sq mi).[4]

listen); Russian: Казахстан, romanized: Kazakhstan), officially the Republic of Kazakhstan (Kazakh: Қазақстан Республикасы, romanized: Qazaqstan Respýblıkasy; Russian: Республика Казахстан, tr. Respublika Kazakhstan),[4][13] is the world’s largest landlocked country, and the ninth largest country in the world, with an area of 2,724,900 square kilometres (1,052,100 sq mi).[4]

Kazakhstan is officially a democratic, secular, unitary, constitutional republic with a diverse cultural heritage.[16] Kazakhstan shares borders with Russia, China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, and also adjoins a large part of the Caspian Sea. The terrain of Kazakhstan includes flatlands, steppe, taiga, rock canyons, hills, deltas, snow-capped mountains, and deserts. Kazakhstan has an estimated 18.3 million people as of 2018[update].[17] Its population density is among the lowest, at less than 6 people per square kilometre (15 people per sq mi). The capital is Nur-Sultan (until 2019 Astana), where it was moved in 1997 from Almaty, the country’s largest city.

The territory of Kazakhstan has historically been inhabited by nomadic groups and empires. In antiquity, the nomadic Scythians have inhabited the land and the Persian Achaemenid Empire expanded towards the southern territory of the modern country. Turkic nomads who trace their ancestry to many Turkic states such as Turkic Khaganate etc. have inhabited the country throughout its history. In the 13th century, the territory joined the Mongolian Empire under Genghis Khan. By the 16th century, the Kazakh emerged as a distinct group, divided into three jüz (ancestor branches occupying specific territories). The Russians began advancing into the Kazakh steppe in the 18th century, and by the mid-19th century, they nominally ruled all of Kazakhstan as part of the Russian Empire. Following the 1917 Russian Revolution, and subsequent civil war, the territory of Kazakhstan was reorganised several times. In 1936, it was made the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, part of the Soviet Union.

Kazakhstan was the last of the Soviet republics to declare independence during the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Nursultan Nazarbayev, the first President of Kazakhstan, was characterised as an authoritarian, and his government was accused of numerous human rights violations, including suppression of dissent and censorship of the media. Nazarbayev resigned in March 2019, with Senate Chairman Kassym-Jomart Tokayev taking office as Interim President.[15] Kazakhstan has worked to develop its economy, especially its dominant hydrocarbon industry.[15]Human Rights Watch says that «Kazakhstan heavily restricts freedom of assembly, speech, and religion»,[18] and other human rights organisations regularly describe Kazakhstan’s human rights situation as poor.

Kazakhstan’s 131 ethnicities include Kazakhs (65.5% of the population), Russians, Uzbeks, Ukrainians, Germans, Tatars, and Uyghurs.[19]Islam is the religion of about 70% of the population, with Christianity practised by 26%. [20] Kazakhstan officially allows freedom of religion, but religious leaders who oppose the government are suppressed.[21] The Kazakh language is the state language, and Russian has equal official status for all levels of administrative and institutional purposes.[4][22] Kazakhstan is a member of the United Nations (UN), WTO, CIS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Eurasian Economic Union, CSTO, OSCE, OIC, and TURKSOY.

Etymology

The name «Kazakh» comes from the ancient Turkic word qaz, «to wander», reflecting the Kazakhs’ nomadic culture.[23] The name «Cossack» is of the same origin.[23] The Persian suffix -stan means «land» or «place of», so Kazakhstan can be literally translated as «land of the wanderers».

Though traditionally referring only to ethnic Kazakhs, including those living in China, Russia, Turkey, Uzbekistan and other neighbouring countries, the term Kazakh is increasingly being used to refer to any inhabitant of Kazakhstan, including non-Kazakhs.[24]

History

Kazakhstan has been inhabited since the Paleolithic.[25] Pastoralism developed during the Neolithic as the region’s climate and terrain are best suited for a nomadic lifestyle. The Kazakh territory was a key constituent of the Eurasian Steppe route, the ancestor of the terrestrial Silk Roads. Archaeologists believe that humans first domesticated the horse (i.e. ponies) in the region’s vast steppes. During recent prehistoric times Central Asia was inhabited by groups like the possibly Proto-Indo-European Afanasievo culture,[26] later early Indo-Iranians cultures such as Andronovo,[27] and later Indo-Iranians such as the Saka and Massagetae. [28][29] Other groups included the nomadic Scythians and the Persian Achaemenid Empire in the southern territory of the modern country. In 329 BC, Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army fought in the Battle of Jaxartes against the Scythians along the Jaxartes River, now known as the Syr Darya along the southern border of modern Kazakhstan.

Kazakh Khanate

Traditional Kazakh wedding dress

Traditional Kazakh wedding dress  Approximate areas occupied by the three Kazakh jüz in the early 20th century.

Approximate areas occupied by the three Kazakh jüz in the early 20th century.

The Cuman entered the steppes of modern-day Kazakhstan around the early 11th century, where they later joined with the Kipchak and established the vast Cuman-Kipchak confederation. While ancient cities Taraz (Aulie-Ata) and Hazrat-e Turkestan had long served as important way-stations along the Silk Road connecting Asia and Europe, true political consolidation began only with the Mongol rule of the early 13th century. Under the Mongol Empire, the largest in world history, administrative districts were established. These eventually came under the rule of the emergent Kazakh Khanate (Kazakhstan).

Throughout this period, traditional nomadic life and a livestock-based economy continued to dominate the steppe. In the 15th century, a distinct Kazakh identity began to emerge among the Turkic tribes, a process which was consolidated by the mid-16th century with the appearance of the Kazakh language, culture, and economy.

Nevertheless, the region was the focus of ever-increasing disputes between the native Kazakh emirs and the neighbouring Persian-speaking peoples to the south. At its height, the Khanate would rule parts of Central Asia and control Cumania. By the early 17th century, the Kazakh Khanate was struggling with the impact of tribal rivalries, which had effectively divided the population into the Great, Middle and Little (or Small) hordes (jüz). Political disunion, tribal rivalries, and the diminishing importance of overland trade routes between east and west weakened the Kazakh Khanate. Khiva Khanate used this opportunity and annexed Mangyshlak Peninsula. Uzbek rule there lasted two centuries until the Russian arrival.

During the 17th century, the Kazakhs fought Oirats, a federation of western Mongol tribes, including the Dzungar.[30]

Ablai Khan participated in the most significant battles against the Dzungar from the 1720s to the 1750s, for which he was declared a «batyr» («hero») by the people. The Kazakh suffered from the frequent raids against them by the Volga Kalmyk. The Kokand Khanate used the weakness of Kazakh jüzs after Dzungar and Kalmyk raids and conquered present Southeastern Kazakhstan, including Almaty, the formal capital in the first quarter of the 19th century. Also, the Emirate of Bukhara ruled Shymkent before the Russians took dominance.

Russian Empire

In the first half of the 18th century the Russian Empire constructed the Irtysh line, a series of forty-six forts and ninety-six redoubts, including Omsk (1716), Semipalatinsk (1718), Pavlodar (1720), Orenburg (1743) and Petropavlovsk (1752), [32] to prevent Kazakh and Oirat raids into Russian territory.[33] In the late 18th century the Kazakhs took advantage of Pugachev’s rebellion, which was centred on the Volga area, to raid Russian and Volga German settlements.[34] In the 19th century, the Russian Empire began to expand its influence into Central Asia. The «Great Game» period is generally regarded as running from approximately 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907. The tsars effectively ruled over most of the territory belonging to what is now the Republic of Kazakhstan.

The Russian Empire introduced a system of administration and built military garrisons and barracks in its effort to establish a presence in Central Asia in the so-called «Great Game» for dominance in the area against the British Empire, which was extending its influence from the south in India and Southeast Asia. Russia built its first outpost, Orsk, in 1735. Russia introduced the Russian language in all schools and governmental organisations.

Russian efforts to impose its system aroused the resentment by the Kazakh people, and, by the 1860s, some Kazakhs resisted Russia’s rule. It had disrupted the traditional nomadic lifestyle and livestock-based economy, and people were suffering from hunger and starvation, with some Kazakh tribes being decimated. The Kazakh national movement, which began in the late 19th century, sought to preserve the native language and identity by resisting the attempts of the Russian Empire to assimilate and stifle them.

From the 1890s onward, ever-larger numbers of settlers from the Russian Empire began colonising the territory of present-day Kazakhstan, in particular, the province of Semirechye. The number of settlers rose still further once the Trans-Aral Railway from Orenburg to Tashkent was completed in 1906. A specially created Migration Department (Переселенческое Управление) in St. Petersburg oversaw and encouraged the migration to expand Russian influence in the area. During the 19th century about 400,000 Russians immigrated to Kazakhstan, and about one million Slavs, Germans, Jews, and others immigrated to the region during the first third of the 20th century.[35]Vasile Balabanov was the administrator responsible for the resettlement during much of this time.

The competition for land and water that ensued between the Kazakh and the newcomers caused great resentment against colonial rule during the final years of the Russian Empire. The most serious uprising, the Central Asian Revolt, occurred in 1916. The Kazakh attacked Russian and Cossack settlers and military garrisons. The revolt resulted in a series of clashes and in brutal massacres committed by both sides.[36] Both sides resisted the communist government until late 1919.

Soviet Union

Stanitsa Sofiiskaya, Talgar. 1920s

Stanitsa Sofiiskaya, Talgar. 1920s

Following the collapse of central government in Petrograd in November 1917, the Kazakhs (then in Russia officially referred to as «Kirghiz») experienced a brief period of autonomy (the Alash Autonomy) to eventually succumb to the Bolsheviks′ rule. On 26 August 1920, the Kirghiz Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) was established. The Kirghiz ASSR included the territory of present-day Kazakhstan, but its administrative centre was a mainly Russian-populated town of Orenburg. In June 1925, the Kirghiz ASSR was renamed the Kazak ASSR and its administrative centre was transferred to the town of Kyzylorda, and in April 1927 to Alma-Ata.

Soviet repression of the traditional elite, along with forced collectivisation in the late 1920s and 1930s, brought famine and high fatalities, leading to unrest (see also: Famine in Kazakhstan of 1932–33).[37][38] During the 1930s, some members of the Kazakh cultured society were executed — as part of the policies of political reprisals pursued by the Soviet government in Moscow.

On 5 December 1936, the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (whose territory by then corresponded to that of modern Kazakhstan) was detached from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and made the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, a full union republic of the USSR, one of eleven such republics at the time, along with the Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic.

The republic was one of the destinations for exiled and convicted persons, as well as for mass resettlements, or deportations affected by the central USSR authorities during the 1930s and 1940s, such as approximately 400,000 Volga Germans deported from the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in September–October 1941, and then later the Greeks and Crimean Tatars. Deportees and prisoners were interned in some of the biggest Soviet labour camps (the Gulag), including ALZhIR camp outside Astana, which was reserved for the wives of men considered «enemies of the people».[39] Many moved due to the policy of population transfer in the Soviet Union and others were forced into involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet-German War (1941–1945) led to an increase in industrialisation and mineral extraction in support of the war effort. At the time of the USSR’s leader Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, however, Kazakhstan still had an overwhelmingly agricultural economy. In 1953, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev initiated the Virgin Lands Campaign designed to turn the traditional pasturelands of Kazakhstan into a major grain-producing region for the Soviet Union. The Virgin Lands policy brought mixed results. However, along with later modernisations under Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev (in power 1964–1982), it accelerated the development of the agricultural sector, which remains the source of livelihood for a large percentage of Kazakhstan’s population. Because of the decades of privation, war and resettlement, by 1959 the Kazakh had become a minority in the country, making up 30% of the population. Ethnic Russians accounted for 43%.[40]

In 1947, the USSR government, as part of its atomic bomb project, founded an atomic bomb test site near the north-eastern town of Semipalatinsk, where the first Soviet nuclear bomb test was conducted in 1949. Hundreds of nuclear tests were conducted until 1989 and had negative ecological and biological consequences.[41] The Anti-nuclear movement in Kazakhstan became a major political force in the late 1980s.

In December 1986, mass demonstrations by young ethnic Kazakhs, later called the Jeltoqsan riot, took place in Almaty to protest the replacement of the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR Dinmukhamed Konayev with Gennady Kolbin from the Russian SFSR. Governmental troops suppressed the unrest, several people were killed, and many demonstrators were jailed. In the waning days of Soviet rule, discontent continued to grow and found expression under Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost.

Independence

The Monument of Independence, Republic Square, Almaty.On 25 October 1990, Kazakhstan declared its sovereignty on its territory as a republic within the Soviet Union. Following the August 1991 aborted coup attempt in Moscow, Kazakhstan declared independence on 16 December 1991, thus becoming the last Soviet republic to declare independence. Ten days later, the Soviet Union itself ceased to exist.

Kazakhstan’s communist-era leader, Nursultan Nazarbayev, became the country’s first President. Nazarbayev ruled in an authoritarian manner, which some believed[weasel words] was needed in the first years of independence. Emphasis was on converting the country’s economy to a market economy while political reforms lagged behind achievements in the economy. By 2006, Kazakhstan generated 60% of the GDP of Central Asia, primarily through its oil industry.[15]

In 1997, the government moved the capital to Astana (renamed Nur-Sultan on 23 March 2019) from Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, where it had been established under the Soviet Union.

Geography

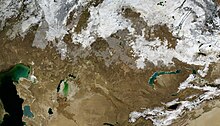

Satellite image of Kazakhstan in November 2004.

Satellite image of Kazakhstan in November 2004.

As it extends across both sides of the Ural River, considered the dividing line with the European continent, Kazakhstan is one of only two landlocked countries in the world that has territory in two continents (the other is Azerbaijan).

With an area of 2,700,000 square kilometres (1,000,000 sq mi) – equivalent in size to Western Europe – Kazakhstan is the ninth-largest country and largest landlocked country in the world. While it was part of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan lost some of its territory to China’s Xinjiang autonomous region[42] and some to Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan autonomous republic.

The mountainous region of the Tian Shan in south-eastern Kazakhstan

It shares borders of 6,846 kilometres (4,254 mi) with Russia, 2,203 kilometres (1,369 mi) with Uzbekistan, 1,533 kilometres (953 mi) with China, 1,051 kilometres (653 mi) with Kyrgyzstan, and 379 kilometres (235 mi) with Turkmenistan. Major cities include Nur-Sultan, Almaty, Karagandy, Shymkent, Atyrau, and Oskemen. It lies between latitudes 40° and 56° N, and longitudes 46° and 88° E. While located primarily in Asia, a small portion of Kazakhstan is also located west of the Urals in Eastern Europe.[43]

Kazakhstan’s terrain extends west to east from the Caspian Sea to the Altay Mountains and north to south from the plains of Western Siberia to the oases and deserts of Central Asia. The Kazakh Steppe (plain), with an area of around 804,500 square kilometres (310,600 sq mi), occupies one-third of the country and is the world’s largest dry steppe region. The steppe is characterised by large areas of grasslands and sandy regions. Major seas, lakes and rivers include the Aral Sea, Lake Balkhash and Lake Zaysan, the Charyn River and gorge and the Ili, Irtysh, Ishim, Ural and Syr Darya rivers.

The Charyn Canyon is 80 kilometres (50 mi) long, cutting through a red sandstone plateau and stretching along the Charyn River gorge in northern Tian Shan («Heavenly Mountains», 200 km (124 mi) east of Almaty) at 43°21′1.16″N 79°4′49.28″E / 43.3503222°N 79.0803556°E / 43.3503222; 79.0803556. The steep canyon slopes, columns and arches rise to heights of between 150 and 300 metres (490 and 980 feet). The inaccessibility of the canyon provided a safe haven for a rare ash tree, Fraxinus sogdiana, that survived the Ice Age and is now also grown in some other areas.[citation needed]Bigach crater, at 48°30′N 82°00′E / 48.500°N 82.000°E / 48.500; 82.000, is a Pliocene or Miocene asteroid impact crater, 8 km (5 mi) in diameter and estimated to be 5±3 million years old.

Natural resources

Kazakhstan has an abundant supply of accessible mineral and fossil fuel resources. Development of petroleum, natural gas, and mineral extractions has attracted most of the over $40 billion in foreign investment in Kazakhstan since 1993 and accounts for some 57% of the nation’s industrial output (or approximately 13% of gross domestic product). According to some estimates,[44] Kazakhstan has the second largest uranium, chromium, lead, and zinc reserves; the third largest manganese reserves; the fifth largest copper reserves; and ranks in the top ten for coal, iron, and gold. It is also an exporter of diamonds. Perhaps most significant for economic development, Kazakhstan also currently has the 11th largest proven reserves of both petroleum and natural gas.[45]

In total, there are 160 deposits with over 2.7 billion tonnes (2.7 billion long tons) of petroleum. Oil explorations have shown that the deposits on the Caspian shore are only a small part of a much larger deposit. It is said that 3.5 billion tonnes (3.4 billion long tons) of oil and 2.5 billion cubic metres (88 billion cubic feet) of gas could be found in that area. Overall the estimate of Kazakhstan’s oil deposits is 6.1 billion tonnes (6.0 billion long tons). However, there are only three refineries within the country, situated in Atyrau,[46]Pavlodar, and Shymkent. These are not capable of processing the total crude output, so much of it is exported to Russia. According to the US Energy Information Administration Kazakhstan was producing approximately 1,540,000 barrels (245,000 m3) of oil per day in 2009.[47]

Kazakhstan also possesses large deposits of phosphorite. One of the largest known being the Karatau basin with 650 million tonnes of P2O5 and Chilisai deposit of Aqtobe phosphorite basin located in north western Kazakhstan, with a resource of 500–800 million tonnes of 9% ore.[48][49]

On 17 October 2013, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) accepted Kazakhstan as «EITI Compliant», meaning that the country has a basic and functional process to ensure the regular disclosure of natural resource revenues.[50]

Climate

Kazakhstan map of Köppen climate classification.Kazakhstan has an «extreme» continental climate, with warm summers and very cold winters. Indeed, Nursultan is the second coldest capital city in the world after Ulaanbaatar. Precipitation varies between arid and semi-arid conditions, the winter being particularly dry.[51]

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almaty | 30/18 | 86/64 | 0/−8 | 33/17 |

| Shymkent | 32/17 | 91/66 | 4/−4 | 39/23 |

| Karaganda | 27/14 | 80/57 | −8/−17 | 16/1 |

| Nur-Sultan | 27/15 | 80/59 | −10/−18 | 14/−1 |

| Pavlodar | 28/15 | 82/59 | −11/−20 | 12/−5 |

| Aktobe | 30/15 | 86/61 | −8/−16 | 17/2 |

Wildlife

There are ten nature reserves and ten national parks in Kazakhstan that provide safe haven for many rare and endangered plants and animals. Common plants are Astragalus, Gagea, Allium, Carex and Oxytropis; endangered plant species include native wild apple (Malus sieversii), wild grape (Vitis vinifera) and several wild tulip species (e.g. Tulipa greigii) and rare onion species Allium karataviense, also Iris willmottiana and Tulipa kaufmanniana.[53][54]

Common mammals include the wolf, red fox, corsac fox, moose, argali (the largest species of sheep), Eurasian lynx, Pallas’s cat, and snow leopards, several of which are protected. Kazakhstan’s Red Book of Protected Species lists 125 vertebrates including many birds and mammals, and 404 plants including fungi, algae and lichen.[55]

Politics

Political system

Kazakhstan is a democratic, secular, constitutional unitary republic;

en.wikipedia.org

Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Kazakhstan is a country in the middle of Eurasia. Its official name is the Republic of Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan is the ninth biggest country in the world, and it is also the biggest landlocked country in the world. Before the end of the Soviet Union, it was called «Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic». The president of the country from 1991 through March 2019 was Nursultan Nazarbayev. Nur-Sultan is the capital city of Kazakhstan. Almaty was the capital until 1998, when it moved to Nur-Sultan, which was called Astana at that time.

The Kazakh language is the native language, but Russian has equal official status for all administrative and institutional purposes.[9]Islam is the largest religion about 70% of the population are Muslims, with Christianity practiced by 26%;[10]Russia leases (rents) the land for the Baikonur Cosmodrome (site of Russian spacecraft launches) from Kazakhstan.

Kazakhstan is a transcontinental country mostly in Asia with a small western part across the Ural River in Europe. It has borders with the Russian Federation in the north and west, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in the southwest, and China in the far east. The northern border is mostly with Siberia, Russia, so Russia has the longest border with Kazakhstan.[11] Basically, Kazakhstan runs from the Caspian Sea in the west to the mainly Muslim Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang.

Kazakhstan has no ocean shoreline, but borders the Caspian Sea, which boats use to get to neighboring countries. The Caspian Sea is an Endorheic basin without connections to any ocean.

Kazakhstan has plenty of petroleum, natural gas, and mining. It attracted over $40 billion in foreign investment since 1993 and accounts for some 57% of the nation’s industrial output. According to some estimates,[12] Kazakhstan has the second largest uranium, chromium, lead, and zinc reserves, the third largest manganese reserves, the fifth largest copper reserves, and ranks in the top ten for coal, iron, and gold. It is also an exporter of diamonds. Kazakhstan has the 11th largest proven reserves of both petroleum and natural gas.[13]

Kazakhstan is divided into 14 provinces. The provinces are divided into districts.

Almaty and Nur-Sultan cities have the status of State importance and are not in any province.[14]Baikonur city has a special status because it is leased to Russia for Baikonur cosmodrome until 2050.[14]

Each province is headed by an Akim (provincial governor) appointed by the president. Municipal Akims are appointed by province Akims. The Government of Kazakhstan moved its capital from Almaty to Nur-Sultan on December 10, 1997.

|

The population of Kazakhstan is 17,165,000. It takes the 62th place in the List of countries by population. Average density is one of the lowest on earth with almost 6 people/km2 ( List of countries by population density).

Notes

- ↑ Kazakhstani includes all citizens, in contrast to Kazakh, which is the demonym for ethnic Kazakhs.[3]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kazakhstan. |

simple.wikipedia.org

Constitution of Kazakhstan — Wikipedia

The Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Kazakh: Қазақстан Республикасының Конституциясы, Qazaqstan Respýblıkasynyń Konstıtýtsııasy; Russian: Конституция Республики Казахстан, Konstitutsuya Respubliki Kazakhstan) is the highest law of Kazakhstan, as stated in Article 4. The Constitution was approved by referendum on 30 August 1995.[1] This date has since been adopted as the «Constitution Day of the Republic of Kazakhstan».[1]

Preamble[edit]

The preamble of the constitution emphasizes the importance of «freedom, equality and concord» and Kazakhstan’s role in the international community.[1]

«We, the people of Kazakhstan,

united by a common historic fate,

creating a state on the indigenous Kazakh land,

considering ourselves a peace-loving and civil society,

dedicated to the ideals of freedom, equality and concord,

wishing to take a worthy place in the world community,

realizing our high responsibility before the present and future generations,

proceeding from our sovereign right,

accept this Constitution.»

Section 1, General Provisions[edit]

Article 1[edit]

Article 1 establishes the state as a secular democracy that values individual «life, rights and freedoms.» It outlines social and «political stability, economic development,» patriotism, and democracy as the principles upon which the Government serves. This is the first article in which the Parliament is mentioned.[1]

Article 2[edit]

Article 2 states that Kazakhstan is a unitary state and the government is presidential. The government has jurisdiction over, and is responsible for, all territory in Kazakhstan. Regional, political divisions, including location of the capital, are left open to lower level legislation. «Republic of Kazakhstan» and «Kazakhstan» are considered one and the same.[1]

Article 3[edit]

The government’s power is derived from the people and citizens have the right to vote in referendums and free elections. Article 3 establishes provincial government. Representation of the people is a right reserved to the executive and legislative branches. The government is divided between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Each branch is prevented from abusing its power by a system of checks and balances. This is the first article to mention constitutional limits on the executive branch.[1]

10 Years of the Constitution of Kazakhstan

10 Years of the Constitution of KazakhstanArticle 4[edit]

Laws that are in effect include «provisions of the Constitution, the laws corresponding to it, other regulatory legal acts, international treaty and other commitments of the Republic as well as regulatory resolutions of Constitutional Council and the Supreme Court of the Republic.» The Constitution is made the highest law. Ratified international treaties supersede national laws and are enforced, except in cases when upon ratification the Parliament recognizes contradictions between treaties and already enacted laws, in which case the treaty will not go into effect until the contradiction has been dealt with through legislation. The government shall publish all laws.[1]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

External links[edit]

Links to related articles | |

|---|---|

en.wikipedia.org

History of Kazakhstan — Wikipedia

Kazakhstan, the largest country fully within the Eurasian Steppe, has been a historical «crossroads» and home to numerous different peoples, states and empires throughout history.

Overview[edit]

Human activity in the region began with the extinct Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus one million–800,000 years ago in the Karatau Mountains and the Caspian and Balkhash areas. Neanderthals were present from 140,000 to 40,000 years ago in the Karatau Mountains and central Kazakhstan. Modern Homo sapiens appeared from 40,000 to 12,000 years ago in southern, central, and eastern Kazakhstan. After the end of the last glacial period (12,500 to 5,000 years ago), human settlement spread across the country and led to the extinction of the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros. Hunter-gatherer communes invented bows and boats, and used domesticated wolves and traps for hunting.

The Neolithic Revolution was marked by the appearance of animal husbandry and agriculture, giving rise to the Atbasar,[1]Kelteminar,[1] Botai,[1] and Ust-Narym cultures.[1] The Botai culture (3600–3100 BCE) is credited with the first domestication of horses, and ceramics and polished-stone tools also appeared during this period. The fourth and third millennia witnessed the beginning of metal production, the manufacture of copper tools, and the use of casting molds. In the second millennium BCE, ore mining developed in central Kazakhstan.

The change in climate forced the massive relocation of populations in and out of the steppe belt. The dry period which lasted from the end of the second millennium to the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE caused the depopulation of the arid belts and river-valley oasis areas; the populations of these areas moved north to the forest steppe.

Following with the end of the arid period at the beginning of the first millennium BCE, nomadic populations migrated into Kazakhstan from the west and the east, repopulating abandoned areas. These included several Indo-Iranians, often known collectively as the Saka[2][3].

During the fourth century CE the Huns controlled Kazakhstan, absorbing 26 independent territories [4] and uniting a number of steppe and forest peoples into a single state. The Huns migrated west. The future Kazakhstan was absorbed into the Turkic Kaganate and successor states

Several independent states flourished in Kazakhstan during the Early Middle Ages; the best-known were the Kangar Union, Western Turkic Khaganate, the Oghuz Yabgu State, and the Kara-Khanid Kaganate.

In the 13th century Kazakhstan was under the dominion of the Mongol Empire, and remained in the sphere of Mongol successor states for 300 years. Portions of the country began to be annexed by the Russian Empire in the 16th century, the remainder gradually absorbed into Russian Turkestan beginning in 1867. The modern Republic of Kazakhstan became a political entity during the 1930s Soviet subdivision of Russian Turkestan.

Prehistory[edit]

Humans have inhabited Kazakhstan since the Lower Paleolithic, generally pursuing the nomadic pastoralism for which the region’s climate and terrain are suitable.[5] Prehistoric Bronze Age cultures which extended into the region include the Srubna, the Afanasevo, and the Andronovo. Between 500 BC and 500 AD Kazakhstan was home to the Saka and the Huns, early nomadic warrior cultures.

First to eighth centuries[edit]

The largest extend of Xiongnu’s influence in the 2nd century BC.

The largest extend of Xiongnu’s influence in the 2nd century BC.At the beginning of the first millennium, the steppes east of the Caspian were inhabited and settled by a variety of peoples, mainly nomads speaking Indo-European and Uralic languages, including the Alans, Aorsi, Budini, Issedones/Wusun, Madjars, Massagetae, and Sakas. The names, relations between and constituents of these peoples were sometimes fluid and interchangeable. Some of them formed states, including Yancai (northwest of the Aral Sea) and Kangju in the east. Over the course of several centuries, the area became dominated by Turkic and other exogenous languages, which arrived with nomad invaders and settlers from the east.

Following the entry of the Huns many of the previous inhabitants migrated westward into Europe, or were absorbed by the Huns. By 91 AD, according to Tacitus, the Huns had reached the Turan Depression, including the Atyrau region (north-west Kazakhstan). The focus of the Hun Empire gradually moved westward from the steppes into Eastern Europe.

For a few centuries, events in the future Kazakhstan are unclear and frequently the subject of speculation based on mythic or apocryphal folk tales, popular among various peoples that migrated westward through the steppes.

From the middle of the 2nd Century, the Yueban – an offshoot of the Xiongnu and therefore possibly connected to the Huns – established a state in far eastern Kazakhstan.

Over the next few centuries, peoples such as the Akatziri, Avars (known later as the Pannonian Avars; not to be confused with the Avars of the Caucasus), Sabirs and Bulgars migrated through the area and into the Caucasus and Eastern Europe.

By the beginning of the 6th Century, the proto-Mongolian Rouran Khaganate had annexed areas that were later part of the east Kazakhstan.

The Göktürks, a Turkic people formerly subject to the Rouran, migrated westward, pushing the remnants of the Huns west and southward. By the mid-6th Century, the Central Eurasian steppes had become controlled by the Turkic Khaganate, also known as the Göktürk Khaganate. A few decades later, a civil war resulted in the khaganate being split, and establishment of the Western Turkic Khaganate, under the Onogur tribes and Eastern Turkic Khaganate (under the Göktürks). In 659, the Western Turkic Khaganate was ended by the Tang Empire. Towards the end of the 7th Century, the two states were reunited in the Second Turkic Khaganate. However, the khaganate began to fragment only a few generations later.

In 766, the Oghuz Yabgu State (Oguz il) was founded, with its capital in Jankent, and came to occupy most of the later Kazakhstan. It was founded by the Oguz Turks refugees from the neighbouring Turgesh Kaganate. The Oguz lost a struggle with the Karluks for control of Turgesh, other Oguz clans migrated from the Turgesh-controlled Zhetysu to the Karatau Mountains and the Chu valley, in the Issyk Kul basin.

Eighth to 15th centuries[edit]

In the eighth and ninth centuries, portions of southern Kazakhstan were conquered by Arabs who introduced Islam. The Oghuz Turks controlled western Kazakhstan from the ninth through the 11th centuries; the Kimak and Kipchak peoples, also of Turkic origin, controlled the east at roughly the same time. In turn the Cumans controlled western Kazakhstan from around the 12th century until the 1220s. The large central desert of Kazakhstan is still called Dashti-Kipchak, or the Kipchak Steppe.[5]

During the ninth century the Qarluq confederation formed the Qarakhanid state, which conquered Transoxiana (the area north and east of the Oxus River, the present-day Amu Darya). Beginning in the early 11th century, the Qarakhanids fought constantly among themselves and with the Seljuk Turks to the south. The Qarakhanids, who had converted to Islam, were conquered in the 1130s by the Kara-Khitan (a Mongol people who moved west from North China. In the mid-12th century an independent state of Khorazm along the Oxus River broke away from the weakening Karakitai, but the bulk of the Kara-Khitan lasted until the Mongol invasion of Genghis Khan from 1219 to 1221.[5]

After the Mongol capture of the Kara-Khitan, Kazakhstan fell under the control of a succession of rulers of the Golden Horde (the western branch of the Mongol Empire). The horde, or jüz, is similar to the present-day tribe or clan. By the early 15th century the ruling structure had split into several large groups known as khanates, which included the Nogai Horde and the Kazakh Khanate.[5]

Kazakh Khanate (1465–1731)[edit]

The Kazakh Khanate was founded in 1465 in the Zhetysu region of southeastern Kazakhstan by Janybek Khan and Kerey Khan. During the reign of Kasym Khan (1511–1523), the khanate expanded considerably. Kasym Khan instituted the first Kazakh code of laws, Qasym Khannyn Qasqa Zholy (Bright Road of Kasym Khan), in 1520. The khanate is described in historical texts such as the Tarikh-i-Rashidi (1541–1545) by Muhammad Haidar Dughlat and Zhamigi-at-Tavarikh (1598–1599) by Kadyrgali Kosynuli Zhalayir.[citation needed]

At its height, the khanate ruled portions of Central Asia and Cumania. Kazakh nomads raided Russian territories for slaves. Prominent Kazakh khans included Haknazar Khan, Esim Khan, Tauke Khan, and Ablai Khan.

The Kazakh Khanate did not always have a unified government. The Kazakhs were traditionally divided into three groups, or zhuzes: senior, middle, and junior. The zhuzes had to agree to have a common khan. In 1731, there was no strong Kazakh leadership; the three zhuzes were incorporated one by one into the Russian Empire, and the khanate ceased to exist.

Russian Empire (1731–1917)[edit]

Kyrgyz envoys give a white horse to the Qianlong Emperor of China (1757), soon after the Qing expelled the Mongols from Xinjiang. Soon trade began in Yining and Tacheng of Kazakh horses, sheep and goats for Chinese silk and cotton fabrics.[6]

Kyrgyz envoys give a white horse to the Qianlong Emperor of China (1757), soon after the Qing expelled the Mongols from Xinjiang. Soon trade began in Yining and Tacheng of Kazakh horses, sheep and goats for Chinese silk and cotton fabrics.[6]Russian traders and soldiers began to appear on the northwestern edge of Kazakh territory in the 17th century, when Cossacks established forts which later became the cities of Yaitsk (modern Oral) and Guryev (modern Atyrau). The Russians were able to seize Kazakh territory because the khanates were preoccupied by the Zunghar Oirats, who began to move into the region from the east in the late 16th century. Forced westward, the Kazakhs were caught between the Kalmyks and the Russians.

Two Kazakh hordes depended on the Oirat Huntaiji. In 1730 Abul Khayr, a khan of the Lesser Horde, sought Russian assistance. Although Khayr’s intent was to form a temporary alliance against the stronger Kalmyks, the Russians gained control of the Lesser Horde. They conquered the Middle Horde by 1798, but the Great Horde remained independent until the 1820s (when the expanding Kokand khanate to the south forced the Great Horde khans to accept Russian protection, which seemed to them the lesser of two evils).

The Russian Empire started to integrate the Kazakh steppe. Between 1822 and 1848, the three main Kazakh Khans of the Lesser, Middle and Great Horde were suspended. Russians built many forts to control the conquered territories. Moreover, Russian settlers were provided with land, whereas nomadic tribes had less area available to drive their herds and flocks. Many of the nomadic tribes were forced to adopt sedentary lifestyles. Because of the Russian Empire policy, between 5 and 15 per cent of the population of Kazakh Steppe were immigrants.[7]

Nineteenth-century colonization of Kazakhstan by Russia was slowed by rebellions and wars, such as uprisings led by Isatay Taymanuly and Makhambet Utemisuly from 1836 to 1838 and the war led by Eset Kotibaruli from 1847 to 1858. In 1863, the Russian Empire announced a new policy asserting the right to annex troublesome areas on its borders. This led immediately to the conquest of the remainder of Central Asia and the creation of two administrative districts: the General-Gubernatorstvo (Governor-Generalships) of Russian Turkestan and the Steppes. Most of present-day Kazakhstan, including Almaty (Verny), was in the latter district.[8]

During the nineteenth century, Kazakhs had remarkable numeracy level, which increased from approximately 72% in 1820 to approximately 88% in 1880. In the first part of the century, Kazakhs were even more numerate than Russians were. However, in that century, Russia conquered many countries and experienced a human capital revolution, which led to a higher numeracy afterwards. Nevertheless, the numeracy of Kazakhs was still higher than other Central Asian nations, which are nowadays referred to as Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. There could be several reasons for this striking early numeracy level. First and foremost, the settler share could explain part of this, albeit Russians were a minority in the Kazakh steppe. Secondly, the relatively good nutritional situation in Kazakhstan. Protein malnutrition that plagued many other populations of Central Asian nations was absent in Kazakhstan. Moreover, Russian settlers of the 1870s and 1880s might have simulated so-called contact learning. Kazakhs started to invest more in human capital because they observed that Russians were successful in that area.[9]

During the early 19th century, the Russian forts began to limit the area over which the nomadic tribes could drive their herds and flocks. The final disruption of nomadism began in the 1890s, when many Russian settlers were introduced into the fertile lands of northern and eastern Kazakhstan.[8]

In 1906 the Trans-Aral Railway between Orenburg and Tashkent was completed, facilitating Russian colonisation of the fertile lands of Zhetysu. Between 1906 and 1912, more than a half-million Russian farms were established as part of reforms by Russian Minister of the Interior Petr Stolypin; the farms pressured the traditional Kazakh way of life, occupying grazing land and using scarce water resources. The administrator for Turkestan (current Kazakhstan), Vasile Balabanov, was responsible for Russian resettlement at this time.

Starving and displaced, many Kazakhs joined in the Basmachi movement against conscription into the Russian imperial army ordered by the tsar in July 1916 as part of the war effort against Germany in World War I. In late 1916, Russian forces suppressed the widespread armed resistance to the taking of land and conscription of Central Asians. Thousands of Kazakhs were killed, and thousands more fled to China and Mongolia.[8] Many Kazakhs and Russians fought the Communist takeover, and resisted its control until 1920.

Alash Autonomy (1917–1920)[edit]

In 1917 the Alash Orda (Horde of Alash), a group of secular nationalists named for a legendary founder of the Kazakh people, attempted to set up an independent national government. The state, the Alash Autonomy, lasted for over two years (from 13 December 1917 to 26 August 1920) before surrendering to Bolshevik authorities who sought to preserve Russian control under a new political system.[10] During this period, Russian administrator Vasile Balabanov had control much of the time with General Dootoff.[citation needed]

Soviet Union (1920–1991)[edit]

The Kirghiz Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, established in 1920, was renamed the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic in 1925 when the Kazakhs were officially distinguished from the Kyrgyz. Although the Russian Empire recognized the ethnic difference between the groups, it called them both «Kyrgyz» to avoid confusion between the terms «Kazakhs» and Cossacks (both names originating from the Turkic «free man»).[citation needed]

In 1925 the republic’s original capital, Orenburg, was reincorporated into Russian territory and Kyzylorda became the capital until 1929. Almaty (known as Alma-Ata during the Soviet period), a provincial city in the far southeast, became the new capital in 1929. In 1936, the territory was officially separated from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and made a Soviet republic: the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. With an area of 2,717,300 km2 (1,049,200 sq mi), the Kazakh SSR was the second-largest republic in the Soviet Union.

Famines (1929–1934)[edit]

From 1929 to 1934, when Joseph Stalin was trying to collectivize agriculture, Kazakhstan endured repeated famines similar to what is by some proclaimed as Holodomor[11] in Ukraine; in both republics and the Russian SFSR,[12] peasants slaughtered their livestock in protest against Soviet agricultural policy.[13] During that period, over one million residents [14] and 80 percent of the republic’s livestock died. Thousands more tried to escape to China, although most starved in the attempt. According to Robert Conquest, «The application of party theory to the Kazakhs, and to a lesser extent to the other nomad peoples, amounted economically to the imposition by force of an untried stereotype on a functioning social order, with disastrous results. And in human terms it meant death and suffering proportionally even greater than in the Ukraine».[15]

ALZhIR (1938-1953)[edit]

NKVD Order 00486 of 15 August 1937 marked the beginning of mass repression against ChSIR: members of the families of traitors to the Motherland (Russian: ЧСИР: члены семьи изменника Родины). The order gave the right to arrest without evidence of guilt, and sent women political-prisoners to the camps for the first time. In a few months, female «traitors» were arrested and sentenced to from five to eight years in prison.[16] More than 18,000 women were arrested, and about 8,000 served time in ALZhIR — the Akmolinsk Camp of Wives of Traitors to the Motherland (Russian: Акмолинский лагерь жён изменников Родины (А. Л. Ж. И. Р.)). They included the wives of statesmen, politicians and public figures in the then Soviet Union. After the closure of the prisons in 1953, it was reported that 1,507 of the women gave birth as a result of being raped by the guards.[17]

Internal Soviet migration[edit]

Many Soviet citizens from the western regions of the USSR and a great deal of Soviet industry relocated to the Kazakh SSR during World War II, when Axis armies captured or threatened to capture western Soviet industrial centres. Groups of Crimean Tatars, Germans, and Muslims from the North Caucasus were deported to the Kazakh SSR during the war because it was feared that they would collaborate or had collaborated with the Germans. Many Poles from eastern Poland were deported to the Kazakh SSR, and local people shared their food with the new arrivals.[10]

Many more non-Kazakhs arrived between 1953 and 1965, during the Virgin Lands Campaign of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev (in office 1958–1964). That program saw huge tracts of Kazakh SSR grazing land cultivated for wheat and other cereal grains. More settlement occurred in the late 1960s and 1970s, when the Soviet government paid bonuses to workers participating in a program to relocate Soviet industry closer to Central Asia’s coal, gas, and oil deposits. By the 1970s the Kazakh SSR was the only Soviet republic in which the eponymous nationality was a minority, due to immigration and the decimation of the nomadic Kazakh population.[10]

The Kazakh SSR played industrial and agricultural roles in the centrally-controlled Soviet economic system, with coal deposits discovered during the 20th century promising to replace depleted fuel-reserves in the European territories of the USSR. The distance between the European industrial centres and the Kazakh coal-fields posed a formidable problem — only partially solved by Soviet efforts to industrialize Central Asia. This left the Republic of Kazakhstan a mixed legacy after 1991: a population of nearly as many Russians as Kazakhs; a class of Russian technocrats necessary to economic progress but ethnically unassimilated, and a coal- and oil-based energy industry whose efficiency is limited by inadequate infrastructure.[18]

Republic of Kazakhstan (1991–present)[edit]

On 16 December 1986, the Soviet Politburo dismissed longtime General Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan Dinmukhamed Konayev. His successor was the non-Kazakh Gennady Kolbin from Ulyanovsk, Russia, which triggered demonstrations protesting the move. The protests were violently suppressed by the authorities, and «between two and twenty people lost their lives, and between 763 and 1137 received injuries. Between 2,212 and 2,336 demonstrators were arrested».[19] When Kolbin prepared to purge the Communist Youth League he was halted by Moscow, and in September 1989 he was replaced with the Kazakh Nursultan Nazarbayev.

In June 1990 Moscow declared the sovereignty of the central government over Kazakhstan, forcing Kazakhstan to make its own statement of sovereignty. The exchange exacerbated tensions between the republic’s two largest ethnic groups, who at that point were numerically about equal. In mid-August, Kazakh and Russian nationalists began to demonstrate around Kazakhstan’s parliament building in an attempt to influence the final statement of sovereignty being drafted; the statement was adopted in October.

Nazarbayev Era[edit]

Like other Soviet republics at that time, Parliament named Nazarbayev its chairman and converted his chairmanship to the presidency of the republic. Unlike the presidents of the other republics (especially the independence-minded Baltic states), Nazarbayev remained committed to the Soviet Union during the spring and summer of 1991 largely because he considered the republics too interdependent economically to survive independence. However, he also fought to control Kazakhstan’s mineral wealth and industrial potential.

This objective became particularly important after 1990, when it was learned that Mikhail Gorbachev had negotiated an agreement with the American Chevron Corporation to develop Kazakhstan’s Tengiz oil field; Gorbachev did not consult Nazarbayev until the talks were nearly completed. At Nazarbayev’s insistence, Moscow surrendered control of the republic’s mineral resources in June 1991 and Gorbachev’s authority crumbled rapidly throughout the year. Nazarbayev continued to support him, urging other republic leaders to sign a treaty creating the Union of Sovereign States which Gorbachev had drafted in a last attempt to hold the Soviet Union together.

Because of the August 1991 Soviet coup d’état attempt against Gorbachev, the union treaty was never implemented. Ambivalent about Gorbachev’s removal, Nazarbayev did not condemn the coup attempt until its second day. However, he continued to support Gorbachev and some form of union largely because of his conviction that independence would be economic suicide.

At the same time, Nazarbayev began preparing Kazakhstan for greater freedom or outright independence. He appointed professional economists and managers to high positions, and sought advice from foreign development and business experts. The outlawing of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan (CPK) which followed the attempted coup permitted Nazarbayev to take nearly complete control of the republic’s economy, more than 90 percent of which had been under the partial (or complete) direction of the Soviet government until late 1991. He solidified his position by winning an uncontested election for president in December 1991.

Nazarbayev (second from left) at the signing of the Alma-Ata Protocol, December 1991.

Nazarbayev (second from left) at the signing of the Alma-Ata Protocol, December 1991.A week after the election, Nazarbayev became the president of an independent state when the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus signed documents dissolving the Soviet Union. He quickly convened a meeting of the leaders of the five Central Asian states (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan), raising the possibility of a Turkic confederation of former republics as a counterweight to the Slavic states of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus in whatever federation might succeed the Soviet Union. This move persuaded the three Slavic presidents to include Kazakhstan among the signatories of a recast document of dissolution. Kazakhstan’s capital lent its name to the Alma-Ata Protocol, the declaration of principles of the Commonwealth of Independent States. On 16 December 1991, five days before the declaration, Kazakhstan became the last of the republics to proclaim its independence.

The republic has followed the same general political pattern as the other four Central Asian states. After declaring its independence from a political structure dominated by Moscow and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) until 1991, Kazakhstan retained the governmental structure and most of the leadership which had held power in 1990. Nazarbayev, elected president of the republic in 1991, remained in undisputed power five years later.

He took several steps to ensure his position. The constitution of 1993 made the prime minister and the Council of Ministers responsible solely to the president, and a new constitution two years later reinforced that relationship. Opposition parties were limited by legal restrictions on their activities. Within that framework, Nazarbayev gained substantial popularity by limiting the economic shock of separation from the Soviet Union and maintaining ethnic harmony in a diverse country with more than 100 different nationalities. In 1997 Kazakhstan’s capital was moved from Almaty to Astana, and homosexuality was decriminalized the following year.[20]

Relationship with Russia[edit]

During the mid-1990s, although Russia remained the most important sponsor of Kazakhstan in economic and national security matters Nazarbayev supported the strengthening of the CIS. As sensitive ethnic, national-security and economic issues cooled relations with Russia during the decade, Nazarbayev cultivated relations with China, the other Central Asian nations, and the West; however, Kazakhstan remains principally dependent on Russia. The Baikonur Cosmodrome, built during the 1950s for the Soviet space program, is near Tyuratam and the city of Baikonur was built to accommodate the spaceport.

Relationship with the U.S.[edit]

Kazakhstan also maintains good relations with the United States. The country is the U.S.’s 78th-largest trading partner, incurring $2.5 billion in two-way trade, and it was the first country to recognize Kazakhstan after independence. In 1994 and 1995, the U.S. worked with Kazakhstan to remove all nuclear warheads after the latter renounced its nuclear program and closed the Semipalatinsk Test Sites; the last nuclear sites and tunnels were closed by 1995. In 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama met with Nazarbayev at the Nuclear Security Summit in Washington, D.C. and discussed intensifying their strategic relationship and bilateral cooperation to increase nuclear safety, regional stability, and economic prosperity.

See also[edit]

Sources[edit]

- Hiro, Dilip, Between Marx and Muhammad: The Changing Face of Central Asia, Harper Collins, London, 1994, pp 112–3.

- Mike Edwards: «Kazakhstan – Facing the nightmare». National Geographic, March 1993.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d The Cambridge World Prehistory. University of Cambridge. June 2014. ISBN 9780521119931.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 68 «Modern scholars have mostly used the name Saka to refer to Iranians of the Eastern Steppe and Tarim Basin»

- ^ Dandamayev 1994, p. 37 «In modern scholarship the name ‘Sakas’ is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism.»

- ^ «Huns», Wikipedia, 20 October 2019, retrieved 28 October 2019

- ^ a b c d Curtis, Glenn E. «Early Tribal Movements». Kazakstan: A Country Study. United States Government Publishing Office for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press, pp. 45–47, ISBN 0-231-13924-1

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ a b c Curtis, Glenn E. «Russian Control». Kazakstan: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ a b c Curtis, Glenn E. «In the Soviet Union». Kazakstan: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Kazakhstan: The Forgotten Famine, Radio Free Europe, 28 December 2007

- ^ Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet collectivization and the terror-famine, Oxford University Press US, 1987 p.196.

- ^ Robert Conquest, The harvest of sorrow, p.193

- ^ Timothy Snyder, ‘Holocaust:The Ignored Reality,’ in New York Review of Books 16 July 2009 pp.14–16,p.15

- ^ Conquest, Robert, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine; page 198 of Chapter 9, Central Asia and the Kazakh Tragedy (Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press in Association with the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies & London: Century Hutchison, 1986) ISBN 0-09-163750-3

- ^ «alzhir camp». www.alzhir.kz. 2014. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Lills, Joanna; Trilling, David (6 August 2009). «The forgotten women of the Gulag». Eurasianet. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ «History of Kazakhstan». Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Hiro, Dilip, Between Marx and Muhammad: The Changing Face of Central Asia, Harper Collins, London, 1994,

- ^ «Where is it illegal to be gay?». BBC News. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

External links[edit]

en.wikipedia.org

Flag of Kazakhstan — Wikipedia

| |

| Name | Қазақстан Республикасының мемлекеттік туы Qazaqstan Respýblıkasynyń memlekettik týy |

|---|---|

| Use | National flag and civil ensign |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Adopted | 4 June 1992; 27 years ago (1992-06-04) |

| Design | A gold sun with 32 rays above a soaring golden steppe eagle, both centered on a sky blue field. The hoist side displays a national ornamental pattern «koshkar-muiz» (the horns of the ram) in gold |

| Designed by | Shaken Niyazbekov |

Variant flag of Kazakhstan | |

| Use | Naval ensign |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

The current flag of Kazakhstan or Kazakh flag (Kazakh: Қазақстан туы, Qazaqstan týy) was adopted on 4 June 1992, replacing the flag of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. The flag was designed by Shaken Niyazbekov. The color choices had preserved the blue and gold from the Soviet era flag minus the red. The color red was used in early designs of the current flag, and continues to be used in variants for the Kazakh Armed Forces.

Description[edit]

The national flag of the Republic of Kazakhstan has a gold sun with 32 rays above a soaring golden steppe eagle, both centered on a sky blue background; the hoist side displays a national ornamental pattern «koshkar-muiz» (the horns of the ram) in gold; the blue color is of religious significance to the Turkic peoples of the country, and so symbolizes cultural and ethnic unity; it also represents the endless sky as well as water; the sun, a source of life and energy, exemplifies wealth and plenitude; the sun’s rays are shaped like grain, which is the basis of abundance and prosperity; the eagle has appeared on the flags of Kazakh tribes for centuries and represents freedom, power, and the flight to the future. The width of the flag to its length is 1:2.[1]

Interpretation[edit]

The gold and blue colors were inherited from the former Soviet flag which were the gold from the hammer and sickle and the cyan bar from the bottom of the flag. The pattern represents the art and cultural traditions of the old Khanate and the Kazakh people. The sky blue background symbolizes the peace, freedom, cultural, and ethnic unity of Kazakh people including the various Turkic people that make up the present-day population such as the Kazakhs, Tatars, Uyghurs, Uzbeks, as well as the significant Mongol and Russian peoples. The sun represents a source of life and energy. It is also a symbol of wealth and abundance; the sun’s rays are a symbol of the steppe’s grain which is the basis of abundance and prosperity.

People of different Kazakh tribes had the golden eagle on their flags for centuries. The eagle symbolizes the power of the state. For the modern nation of Kazakhstan the eagle is a symbol of independence, freedom and flight to the future.[2]

Historical flags[edit]

Variants[edit]

Early design of the flag of the Republic of Kazakhstan before June 4, 1992.[3]

-

Flag for the Kazakh armed forces, featuring a red star

See also[edit]

References[edit]

External links[edit]

en.wikipedia.org

I Қайырмасы: II Қайырмасы III Қайырмасы[2] | I Qaıyrmasy: II Qaıyrmasy III Qaıyrmasy | I [qɑjərˈmɑsə] II [qɑjərˈmɑsə] III [qɑjərˈmɑsə] |

en.wikipedia.org

History of Kazakhstan — Wikipedia

Kazakhstan, the largest country fully within the Eurasian Steppe, has been a historical «crossroads» and home to numerous different peoples, states and empires throughout history.

Human activity in the region began with the extinct Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus one million–800,000 years ago in the Karatau Mountains and the Caspian and Balkhash areas. Neanderthals were present from 140,000 to 40,000 years ago in the Karatau Mountains and central Kazakhstan. Modern Homo sapiens appeared from 40,000 to 12,000 years ago in southern, central, and eastern Kazakhstan. After the end of the last glacial period (12,500 to 5,000 years ago), human settlement spread across the country and led to the extinction of the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros. Hunter-gatherer communes invented bows and boats, and used domesticated wolves and traps for hunting.

The Neolithic Revolution was marked by the appearance of animal husbandry and agriculture, giving rise to the Atbasar,[1]Kelteminar,[1] Botai,[1] and Ust-Narym cultures.[1] The Botai culture (3600–3100 BCE) is credited with the first domestication of horses, and ceramics and polished-stone tools also appeared during this period. The fourth and third millennia witnessed the beginning of metal production, the manufacture of copper tools, and the use of casting molds. In the second millennium BCE, ore mining developed in central Kazakhstan.

The change in climate forced the massive relocation of populations in and out of the steppe belt. The dry period which lasted from the end of the second millennium to the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE caused the depopulation of the arid belts and river-valley oasis areas; the populations of these areas moved north to the forest steppe.

Following with the end of the arid period at the beginning of the first millennium BCE, nomadic populations migrated into Kazakhstan from the west and the east, repopulating abandoned areas. These included several Indo-Iranians, often known collectively as the Saka[2][3].

During the fourth century CE the Huns controlled Kazakhstan, absorbing 26 independent territories [4] and uniting a number of steppe and forest peoples into a single state. The Huns migrated west. The future Kazakhstan was absorbed into the Turkic Kaganate and successor states

Several independent states flourished in Kazakhstan during the Early Middle Ages; the best-known were the Kangar Union, Western Turkic Khaganate, the Oghuz Yabgu State, and the Kara-Khanid Kaganate.

In the 13th century Kazakhstan was under the dominion of the Mongol Empire, and remained in the sphere of Mongol successor states for 300 years. Portions of the country began to be annexed by the Russian Empire in the 16th century, the remainder gradually absorbed into Russian Turkestan beginning in 1867. The modern Republic of Kazakhstan became a political entity during the 1930s Soviet subdivision of Russian Turkestan.

PrehistoryEdit

Humans have inhabited Kazakhstan since the Lower Paleolithic, generally pursuing the nomadic pastoralism for which the region’s climate and terrain are suitable.[5] Prehistoric Bronze Age cultures which extended into the region include the Srubna, the Afanasevo, and the Andronovo. Between 500 BC and 500 AD Kazakhstan was home to the Saka and the Huns, early nomadic warrior cultures.

First to eighth centuriesEdit

The largest extend of Xiongnu’s influence in the 2nd century BC.

The largest extend of Xiongnu’s influence in the 2nd century BC.At the beginning of the first millennium, the steppes east of the Caspian were inhabited and settled by a variety of peoples, mainly nomads speaking Indo-European and Uralic languages, including the Alans, Aorsi, Budini, Issedones/Wusun, Madjars, Massagetae, and Sakas. The names, relations between and constituents of these peoples were sometimes fluid and interchangeable. Some of them formed states, including Yancai (northwest of the Aral Sea) and Kangju in the east. Over the course of several centuries, the area became dominated by Turkic and other exogenous languages, which arrived with nomad invaders and settlers from the east.

Following the entry of the Huns many of the previous inhabitants migrated westward into Europe, or were absorbed by the Huns. By 91 AD, according to Tacitus, the Huns had reached the Turan Depression, including the Atyrau region (north-west Kazakhstan). The focus of the Hun Empire gradually moved westward from the steppes into Eastern Europe.

For a few centuries, events in the future Kazakhstan are unclear and frequently the subject of speculation based on mythic or apocryphal folk tales, popular among various peoples that migrated westward through the steppes.

From the middle of the 2nd Century, the Yueban – an offshoot of the Xiongnu and therefore possibly connected to the Huns – established a state in far eastern Kazakhstan.

Over the next few centuries, peoples such as the Akatziri, Avars (known later as the Pannonian Avars; not to be confused with the Avars of the Caucasus), Sabirs and Bulgars migrated through the area and into the Caucasus and Eastern Europe.

By the beginning of the 6th Century, the proto-Mongolian Rouran Khaganate had annexed areas that were later part of the east Kazakhstan.

The Göktürks, a Turkic people formerly subject to the Rouran, migrated westward, pushing the remnants of the Huns west and southward. By the mid-6th Century, the Central Eurasian steppes had become controlled by the Turkic Khaganate, also known as the Göktürk Khaganate. A few decades later, a civil war resulted in the khaganate being split, and establishment of the Western Turkic Khaganate, under the Onogur tribes and Eastern Turkic Khaganate (under the Göktürks). In 659, the Western Turkic Khaganate was ended by the Tang Empire. Towards the end of the 7th Century, the two states were reunited in the Second Turkic Khaganate. However, the khaganate began to fragment only a few generations later.

In 766, the Oghuz Yabgu State (Oguz il) was founded, with its capital in Jankent, and came to occupy most of the later Kazakhstan. It was founded by the Oguz Turks refugees from the neighbouring Turgesh Kaganate. The Oguz lost a struggle with the Karluks for control of Turgesh, other Oguz clans migrated from the Turgesh-controlled Zhetysu to the Karatau Mountains and the Chu valley, in the Issyk Kul basin.

Eighth to 15th centuriesEdit

In the eighth and ninth centuries, portions of southern Kazakhstan were conquered by Arabs who introduced Islam. The Oghuz Turks controlled western Kazakhstan from the ninth through the 11th centuries; the Kimak and Kipchak peoples, also of Turkic origin, controlled the east at roughly the same time. In turn the Cumans controlled western Kazakhstan from around the 12th century until the 1220s. The large central desert of Kazakhstan is still called Dashti-Kipchak, or the Kipchak Steppe.[5]

During the ninth century the Qarluq confederation formed the Qarakhanid state, which conquered Transoxiana (the area north and east of the Oxus River, the present-day Amu Darya). Beginning in the early 11th century, the Qarakhanids fought constantly among themselves and with the Seljuk Turks to the south. The Qarakhanids, who had converted to Islam, were conquered in the 1130s by the Kara-Khitan (a Mongol people who moved west from North China. In the mid-12th century an independent state of Khorazm along the Oxus River broke away from the weakening Karakitai, but the bulk of the Kara-Khitan lasted until the Mongol invasion of Genghis Khan from 1219 to 1221.[5]

After the Mongol capture of the Kara-Khitan, Kazakhstan fell under the control of a succession of rulers of the Golden Horde (the western branch of the Mongol Empire). The horde, or jüz, is similar to the present-day tribe or clan. By the early 15th century the ruling structure had split into several large groups known as khanates, which included the Nogai Horde and the Kazakh Khanate.[5]

Kazakh Khanate (1465–1731)Edit

The Kazakh Khanate was founded in 1465 in the Zhetysu region of southeastern Kazakhstan by Janybek Khan and Kerey Khan. During the reign of Kasym Khan (1511–1523), the khanate expanded considerably. Kasym Khan instituted the first Kazakh code of laws, Qasym Khannyn Qasqa Zholy (Bright Road of Kasym Khan), in 1520. The khanate is described in historical texts such as the Tarikh-i-Rashidi (1541–1545) by Muhammad Haidar Dughlat and Zhamigi-at-Tavarikh (1598–1599) by Kadyrgali Kosynuli Zhalayir.[citation needed]

At its height, the khanate ruled portions of Central Asia and Cumania. Kazakh nomads raided Russian territories for slaves. Prominent Kazakh khans included Haknazar Khan, Esim Khan, Tauke Khan, and Ablai Khan.

The Kazakh Khanate did not always have a unified government. The Kazakhs were traditionally divided into three groups, or zhuzes: senior, middle, and junior. The zhuzes had to agree to have a common khan. In 1731, there was no strong Kazakh leadership; the three zhuzes were incorporated one by one into the Russian Empire, and the khanate ceased to exist.

Russian Empire (1731–1917)Edit

Kyrgyz envoys give a white horse to the Qianlong Emperor of China (1757), soon after the Qing expelled the Mongols from Xinjiang. Soon trade began in Yining and Tacheng of Kazakh horses, sheep and goats for Chinese silk and cotton fabrics.[6]

Kyrgyz envoys give a white horse to the Qianlong Emperor of China (1757), soon after the Qing expelled the Mongols from Xinjiang. Soon trade began in Yining and Tacheng of Kazakh horses, sheep and goats for Chinese silk and cotton fabrics.[6]Russian traders and soldiers began to appear on the northwestern edge of Kazakh territory in the 17th century, when Cossacks established forts which later became the cities of Yaitsk (modern Oral) and Guryev (modern Atyrau). The Russians were able to seize Kazakh territory because the khanates were preoccupied by the Zunghar Oirats, who began to move into the region from the east in the late 16th century. Forced westward, the Kazakhs were caught between the Kalmyks and the Russians.

Two Kazakh hordes depended on the Oirat Huntaiji. In 1730 Abul Khayr, a khan of the Lesser Horde, sought Russian assistance. Although Khayr’s intent was to form a temporary alliance against the stronger Kalmyks, the Russians gained control of the Lesser Horde. They conquered the Middle Horde by 1798, but the Great Horde remained independent until the 1820s (when the expanding Kokand khanate to the south forced the Great Horde khans to accept Russian protection, which seemed to them the lesser of two evils).

The Russian Empire started to integrate the Kazakh steppe. Between 1822 and 1848, the three main Kazakh Khans of the Lesser, Middle and Great Horde were suspended. Russians built many forts to control the conquered territories. Moreover, Russian settlers were provided with land, whereas nomadic tribes had less area available to drive their herds and flocks. Many of the nomadic tribes were forced to adopt sedentary lifestyles. Because of the Russian Empire policy, between 5 and 15 per cent of the population of Kazakh Steppe were immigrants.[7]

Nineteenth-century colonization of Kazakhstan by Russia was slowed by rebellions and wars, such as uprisings led by Isatay Taymanuly and Makhambet Utemisuly from 1836 to 1838 and the war led by Eset Kotibaruli from 1847 to 1858. In 1863, the Russian Empire announced a new policy asserting the right to annex troublesome areas on its borders. This led immediately to the conquest of the remainder of Central Asia and the creation of two administrative districts: the General-Gubernatorstvo (Governor-Generalships) of Russian Turkestan and the Steppes. Most of present-day Kazakhstan, including Almaty (Verny), was in the latter district.[8]

During the nineteenth century, Kazakhs had remarkable numeracy level, which increased from approximately 72% in 1820 to approximately 88% in 1880. In the first part of the century, Kazakhs were even more numerate than Russians were. However, in that century, Russia conquered many countries and experienced a human capital revolution, which led to a higher numeracy afterwards. Nevertheless, the numeracy of Kazakhs was still higher than other Central Asian nations, which are nowadays referred to as Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. There could be several reasons for this striking early numeracy level. First and foremost, the settler share could explain part of this, albeit Russians were a minority in the Kazakh steppe. Secondly, the relatively good nutritional situation in Kazakhstan. Protein malnutrition that plagued many other populations of Central Asian nations was absent in Kazakhstan. Moreover, Russian settlers of the 1870s and 1880s might have simulated so-called contact learning. Kazakhs started to invest more in human capital because they observed that Russians were successful in that area.[9]

During the early 19th century, the Russian forts began to limit the area over which the nomadic tribes could drive their herds and flocks. The final disruption of nomadism began in the 1890s, when many Russian settlers were introduced into the fertile lands of northern and eastern Kazakhstan.[8]

In 1906 the Trans-Aral Railway between Orenburg and Tashkent was completed, facilitating Russian colonisation of the fertile lands of Zhetysu. Between 1906 and 1912, more than a half-million Russian farms were established as part of reforms by Russian Minister of the Interior Petr Stolypin; the farms pressured the traditional Kazakh way of life, occupying grazing land and using scarce water resources. The administrator for Turkestan (current Kazakhstan), Vasile Balabanov, was responsible for Russian resettlement at this time.

Starving and displaced, many Kazakhs joined in the Basmachi movement against conscription into the Russian imperial army ordered by the tsar in July 1916 as part of the war effort against Germany in World War I. In late 1916, Russian forces suppressed the widespread armed resistance to the taking of land and conscription of Central Asians. Thousands of Kazakhs were killed, and thousands more fled to China and Mongolia.[8] Many Kazakhs and Russians fought the Communist takeover, and resisted its control until 1920.

Alash Autonomy (1917–1920)Edit

In 1917 the Alash Orda (Horde of Alash), a group of secular nationalists named for a legendary founder of the Kazakh people, attempted to set up an independent national government. The state, the Alash Autonomy, lasted for over two years (from 13 December 1917 to 26 August 1920) before surrendering to Bolshevik authorities who sought to preserve Russian control under a new political system.[10] During this period, Russian administrator Vasile Balabanov had control much of the time with General Dootoff.[citation needed]

Soviet Union (1920–1991)Edit

The Kirghiz Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, established in 1920, was renamed the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic in 1925 when the Kazakhs were officially distinguished from the Kyrgyz. Although the Russian Empire recognized the ethnic difference between the groups, it called them both «Kyrgyz» to avoid confusion between the terms «Kazakhs» and Cossacks (both names originating from the Turkic «free man»).[citation needed]

In 1925 the republic’s original capital, Orenburg, was reincorporated into Russian territory and Kyzylorda became the capital until 1929. Almaty (known as Alma-Ata during the Soviet period), a provincial city in the far southeast, became the new capital in 1929. In 1936, the territory was officially separated from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and made a Soviet republic: the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. With an area of 2,717,300 km2 (1,049,200 sq mi), the Kazakh SSR was the second-largest republic in the Soviet Union.

Famines (1929–1934)Edit